(CNN) -- The battle over hydraulic fracturing in the state of New York pits farmers against environmentalists, neighbor vs. neighbor, as gas companies wait to find out if they'll be able to unlock the natural gas trapped in the Marcellus Shale formation thousands of feet below the earth's surface.

As a panel appointed by New York's governor looks into whether it can be done safely in New York, landowners look with envy toward neighboring Pennsylvania, where gas companies are paying in excess of $1,000 per acre plus royalties for the right to drill for natural gas on a property.

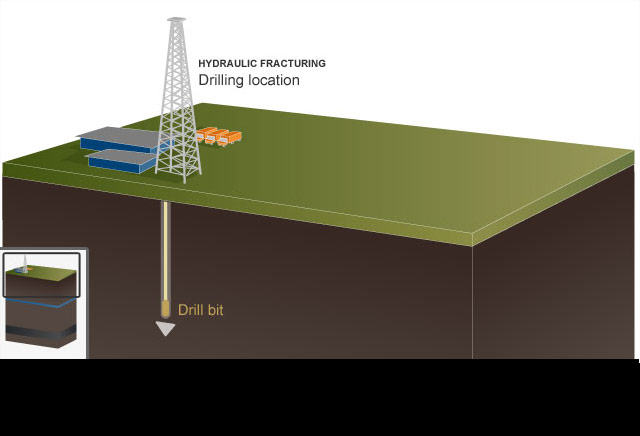

Hydraulic fracturing, commonly known as fracking, involves injecting a mixture of water and chemicals deep into the earth. The pressure causes shale rock formations to fracture and natural gas is released in the process. The fluid is then extracted and the natural gas is mined through the well. Some fracking operations have been linked to the contamination of drinking water supplies, and that led to a moratorium on hydraulic fracturing in New York.

Judy Whittaker hopes to one day have a drilling rig on her property if and when that moratorium is lifted. The 1,000-acre dairy farm in Whitney Point, a small town in rural northwest New York, has been in her family for more than 100 years.

"We hope that our farm would be able to be sustainable in the future ... for our grandchildren to be able to be here and make a profit at farming, at the thing that we all love," said Whittaker.

While Whittaker's family has been milking cows for four generations, they still struggle to get by year after year. The added income from a natural gas lease on her property holds the promise of financial security.

"If we were able to get natural gas drilling I think it would definitely make a less stressful life for those in the future that are on this farm, not having to worry so much about the price of milk and where the money is coming from," said Whittaker. "They would have something to fall back on."

The opposition to fracking

Opponents of fracking raise concerns about its impact on drinking water. Whittaker isn't worried. "I believe that we know our land the best so we ought to be the ones choosing the best use for our land."

She said she's confident that with proper oversight fracking can be done safely.

"I'm very comfortable with the regulations that they are proposing. It's tough laws now and it's going to be even tougher if implemented fully the way it will be."

No one says a fracking operation is completely risk free. About an hour's drive southeast of Whittaker's farm lies New York City's protected watershed in the Catskill Mountains. It's part of the source of 1.1 billion gallons of water that flows to the city each day.

"It's too much of a risk ... not a risk the city of New York is willing to take," said Paul Rush, deputy commissioner at the New York City Department of Environmental Protection. It's his job to assure that every drop of water that makes it to a faucet in New York is as clean as possible.

"We have 19 reservoirs and three controlled lakes in the New York City system with a capacity of 580 billion gallons."

As Rush watched water pouring into the massive Rondout Reservoir, he said, "The possibility of chemicals getting into the water table, the possibility of chemical spills in the watershed itself, the disturbances in the watershed changing the character of it, deforestation for the construction of roads, are all potential impacts on our system."

The Department of Environmental Protection does not use water filtration systems. Instead, it relies on natural filtration and keeping the water clean at the source. It only adds a few chemicals, to kill any remaining pathogens and to strengthen tooth enamel, before water reaches faucets in the city 100 miles away. It's some of the cleanest municipal drinking water in the world and in order to keep it that way, the governor's panel on fracking is effectively banning gas mining in the New York City watershed.

New York governor pauses 'fracking'

The debate over fracking in New York is heated. More than 65,000 comments were submitted by the public during the state's environmental review process. Kate Sinding, an attorney with the environmental group the National Resources Defense Council, is among those leading the fight against fracking.

"What we've seen in state after state is that as this activity comes into the places where people live, comes into communities, there are tremendous impacts or potential impacts on people's drinking-water supplies if it's not properly regulated or evaluated," Sinding said.

New Yorkers only have to look over the border in Pennsylvania to find an example of a fracking operation gone wrong.

"In the community of Dimock, Pennsylvania," Sinding said, "an aquifer was contaminated by bad drilling and fracking practices by a gas company. In addition to which there were a huge number of spills. It was a sort of horror story of what goes wrong when an industry isn't effectively regulated."

A pair of university studies that came out over the past few months, one from the University of Texas and the other from Stanford, showed the process of fracking itself doesn't appear to pose a risk to drinking water. The studies found no record of a drinking water supply being contaminated by fracking fluids injected into shale formations several thousand feet below the Earth's surface. But the studies reported that shoddy drilling practices, accidents and poor oversight above ground have led to contaminated water wells.

"I'm not trying to deny the existence of contamination, but the mechanism by which that contamination occurred is not the hydraulic fracturing mechanism," said Mark Zoback, a geophysics professor at Stanford University who studied this form of drilling for natural gas. He also served on the Energy Department's committee that examined fracking.

While tens of thousands of gas wells have been drilled across the country in recent years, he says there have been relatively few cases of chemicals contaminating drinking water supplies. "The number is more like dozens," said Zoback.

University of Texas Geologist Chip Groat also studied fracking. His findings back up much of what Zoback reported.

"We didn't find (anything) happening related to shale gas that called for draconian measures in terms of regulations or prohibitions," Groat said.

Sinding believes Zoback's and Groat's findings don't reflect reality. She says in many states regulators have close relationships with the gas industry and they don't fully investigate claims of contamination.

"The other issue is one of the gas companies settling with people and then subjecting them to nondisclosure agreements, which is the industry standard." Sinding said such arrangements result in cases of contamination not being fully reported to local municipalities.

Sinding and Zoback agree on one thing: The best way to assure that there is no contamination from a fracking operation is to make sure there are very stringent guidelines in place and that the drilling companies are closely monitored by state agencies with frequent inspections.

"That seems rather mundane," Zoback said, "but the way the well is drilled, cased and cemented, the way those processes are required and regulated and inspected and assured, are the most important things we can do to prevent potential problems either in the near term or the long term."

While multiple studies found no evidence of water wells contaminated by chemicals injected into shale formations several miles below ground, the National Academy of Sciences reported findings that show an increase of methane gas in some water wells near fracking operations across the country. The academy recommended more testing be done to determine the "potential health consequences of methane" and increased testing of water wells as well as strong regulations for fracking operations.

Addressing the issues

Drilling companies say they've taken steps over the past few years to address these concerns. "The industry I think is in a far better place today than we were many years ago," said Matt Pitzarella, a spokesman for Range Resources, one of several companies mining Marcellus Shale natural gas in Pennsylvania.

"There's a cartoon character out there that we are somehow a bunch of Texans that are poking holes in the ground and hoping that we strike it rich," said Pitzarella. But he said that's not the case. Range Resources was the first company to drill for gas in the Marcellus Shale formation in Pennsylvania.

What is 'fracking'?

What is 'fracking'?Oil and gas drilling is not a recent development in the state. "There are 384,000 oil and gas wells that have been drilled in the state of Pennsylvania and more than 150,000 of those wells have been hydraulically fractured," said Pitzarella. He said he believes drilling techniques have improved dramatically over the past few years, especially as they pertain to isolating the drilling operation from the surrounding layers of rock and sediment.

2010: Water contaminated by 'fracking'?

2010: Water contaminated by 'fracking'?"You are now required to have multiple layers, four layers of steel that is fully encased in concrete all the way down (the) hole, all the way up to the surface," said Pitzarella. "There's 3 million pounds of steel and concrete that travel literally tens of thousands of feet." The state requires testing throughout the process.

2010: Fear in Northeast over 'Fracking'

2010: Fear in Northeast over 'Fracking'Pitzarella said his company has every incentive to drill in a safe way and not affect the environment. "We can only drill if people are choosing to sign leases with us. So if the general public is not comfortable with it they're not going to sign a lease."

Actor Mark Ruffalo fights fracking

Actor Mark Ruffalo fights frackingPitzarella said there could be cases of methane gas migrating into water wells, but, "You're talking about fractions of a percent of likelihood." He said many water wells in Pennsylvania already contained methane gas before drilling started. Drilling companies are now required to test local water wells before any gas mining takes place. "What we find is that more than half ... already have methane in the water," and Pitzarella said it was naturally occurring.

There are concerns that state agencies aren't equipped to properly oversee fracking operations, especially when one considers how quickly they dot the landscape once an area has been opened to drilling for natural gas.

"You might ask questions about the intensity of the development, the rate of the development and the capacity of the existing regulatory agencies," Groat said, "to put the human power into the inspections and into the surveillance that needs to be there."

That's why the defense council's Sinding is trying to place strict limits and guidelines on fracking in New York. "We think this is just an area where being as cautious as possible is the only course that makes any sense."

Other than water contamination, drilling for natural gas raises another concern: A few, small, repeated earthquakes have been linked to some aspects of a fracking operation. Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Oberservatory found that several small earthquakes near Youngstown, Ohio, in 2011 were likely caused by the injection of fracking wastewater into containment wells deep below ground. Scientists in England believe hydraulic fracturing triggered several small earthquakes near Blackpool in the northwest of the country last year. "They are extremely small earthquakes," said Zoback. "Magnitude 2 earthquakes are almost never even felt."

"Things can move around and there are faults that we know cross our tunnel. We have maps that show those," said New York's Rush. "What we found was there's not a direct risk to have a major event that could cause a total collapse of a tunnel but there is a potential for damage to our infrastructure."

One of the city's water tunnels, the Delaware Aqueduct, already had some cracks before fracking started. At 85 miles, it's the longest tunnel in the world. Rush is concerned that repeated shaking could cause more damage and foul the water running through it.

The Department of Environmental Protection is recommending to the governor's panel examining fracking that no drilling be allowed within 2 miles of any water tunnel. The National Resources Defense Council would like that ban to be extended to 7 miles.

Other questions have been raised about fracking. Environmentalists express concerns over whether the hydraulic fluid that remains in a shale formation after the natural gas has been extracted could migrate into the water table even though the two are often separated by several miles of bedrock.

While farmers in economically depressed regions of New York await the fracking panel's recommendations, some communities have banned fracking. In late February, a New York state judge ruled that the town of Dreyden could bar the practice in its municipality.

That's troubling for farmers like Whittaker, who see fracking as a way to keep agriculture viable in tough economic times. "We want what's best for the future of our land, for the future of our lands," Whittaker said, "so that our grandchildren can have a farm here."

Natural gas mining would not be an endless source of income for farmers like Whittaker, though. Estimates vary as to how much natural gas is locked in the Marcellus Shale formation. The U.S. Department of Energy reported there is the potential for a 100 year supply of natural gas to be unlocked from shale rock formations across the country.

In the end, New York's panel on fracking will have to determine how much risk is acceptable in exchange for the promise of economic gain.

http://www.cnn.com/2012/03/09/us/new-york-fracking/index.html